WarioWare Thrives on Individuality

Fair warning: Wario is my role model for life

When it comes to WarioWare, the word that reflexively kicks to the front of my mind is “unique.” The more I think about it, however, the less sense it makes to describe it that way. “Unique” only identifies a vague concept. It only scratches the surface. WarioWare sticks with me less because it is unique, and more because of why it is unique. If you really dig into the core of WarioWare, what makes these games interesting is how they rely on and push the individual to the forefront. You, me, the developers, the cast of the game, and especially Wario. Perhaps we are all Wario, in our own way.

Yeah, I know. Finally, some existential writing about Wario.

I find “unique” to be one of the most dangerous words in a writer’s vocabulary, particularly when talking about video games. It may not be intentional, but using it gives a certain impression – “nothing else has ever been like this!” It’s as if whatever game getting described as unique suddenly formed from a void of nothingness. I understand the temptation to label things you’ve never seen before as unique, but uniqueness in the never-before-existed sense is a harder case to prove than most give credit. In truth, virtually everything builds on things that already exist.

That’s also true for WarioWare. Nintendo’s developers state that the concept grew out of “Sound Bomber,” an extra side mode from a Mario art game on the Nintendo 64DD that functions almost identically to WarioWare. Games like Point Blank, Bishi Bashi, and Ichidant-R explored the concept of assaulting players with barrages of mini games long before that. If you want to get more abstract, the simple concept of throwing different “bonus” modes or styles of play in between “normal” game segments could be seen as building blocks leading up to WarioWare.

I’m not saying this to take anything away from WarioWare. It adds its own twists to the “assault with mini games” concept. That’s actually the point. When it comes to uniqueness, you’ll find more success talking about these smaller quirks or twists than claiming wholesale innovation. I hear the uniqueness purists loud and clear, though: if your criteria for measuring uniqueness relies on little things like that, wouldn’t that mean everything is unique?

Pretty much. After all, we all may be humans (or at least I assume, feel free to correct me) but we also have our own personalities, appearances, and traits that differentiate us. WarioWare thrives on that kind of uniqueness more than anything else.

When it comes to Nintendo, people tend to generalize. “Nintendo games” sometimes get treated like their own subgenre, as if there’s certain things that are uniquely “Nintendo,” giving the company name itself more weight than the individuals who actually made the game. To some extent it’s true – Nintendo games generally have certain standards they need to meet and I get the sense that the higher-ups are strict about that. Unless you’re the kind of superfan who follows developers and reads interviews, it can be difficult to pick out the actual individuals involved underneath the layers of Nintendo polish.

WarioWare differs from the typical “Nintendo game” by shouting out the individual contributions loud and clear. The microgames function as a conduit connecting the player to the individuals who made the game.

When developing WarioWare games, everyone on the staff had the opportunity to contribute their own microgame ideas. They’d draw their idea on a sticky note, put it up on a board, and the programmers selected ones they wanted to implement. Knowing this, a lot about WarioWare starts to make sense. The lack of consistency in the aesthetics, the shifting tones, the wacky senses of humor. Each and every microgame contains a little bit of the individual who made it.

One of my favorite details in WarioWare microgames is how they evolve as you level up. Apparently, the person who came up with the game also had to figure out how to change them for each level. Since the microgames are so short, having to expand on them to make them harder requires some ingenuity. More importantly, it requires getting into the head of the player.

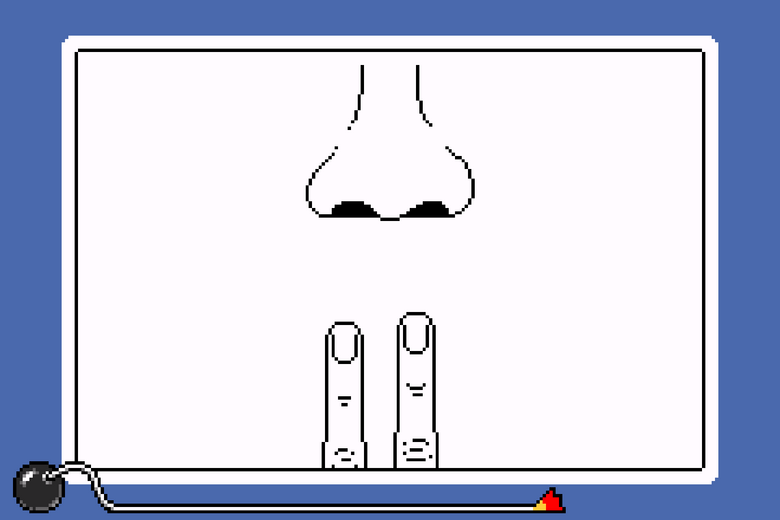

Sometimes the difficulty increase feels more traditional. The nose picking mini game goes from using your thin pinky, to a thicker index finger, until finally asking you to attempt a twofer. At other times the games play on your expectations in more unusual ways. One game asks Wario to jump over the hot dog car. On the highest difficulty, however, the hot dog car can jump over him, requiring the player to think on their feet and do the exact opposite of what they had been taught prior.

Game design could be thought of as the way developers communicate with players. In that case, WarioWare may be the video game equivalent of speed dating. In a typical microgame, you learn how to play, get a glimpse of the developer’s personality, and then move on immediately. If you ever happen to see that microgame again at a higher level, you take what you know and then learn even more about that person by how they twist their concept to further challenge and amuse you.

It only makes sense that so many people get to talk with you. You are also an important part of the WarioWare experience.

While it remains a little vague, my read on the original WarioWare scenario was always that you were considered part of Wario’s crew. The game lets you name yourself, all of the characters address you directly, and you access all of the games on what appears to be an office computer. You may be the one paying in order to play, but it’s like Wario hired you in particular to playtest all of these games. The final product only goes on sale in-universe once you’ve beaten all the games, after all.

By implementing you directly into the game, WarioWare solidifies your own individuality. This small nod suggests that not only were the individuals who made each microgame important, but the player who cares enough to complete them all is too. We’re all in this odd little corporate venture together. Everyone, real and the virtual, works for Wario at the end of the day.

Wario’s virtual crew closely resembles the real life development situation of the game. In-universe, the microgames have been split into sets based on which crew member made them. Each of Wario’s friends display strong personalities and the microgames are meant to reflect that. Jimmy T. likes sports, Mona loves strange things, 9-Volt buries himself in retro games, and so on.

Implementing Wario’s friends and their loose narratives adds a layer of personality to the game that brings the WarioWare experience together perfectly. They cleverly adapt the real life circumstances of game development by humanizing the microgames in a way that even kids are likely to understand. You aren’t just playing some random nose-picking game, you’re playing Mona’s nose-picking game. Those puzzle microgames are more challenging because they were made by an incomprehensible extraterrestrial specimen. It all makes sense, as long as you don’t stop to think about anything for too long.

Wario himself could not have been a more perfect character for the kind of game WarioWare ended up being. To me, he is the posterchild of strong characters carried by their individuality. We’re talking about a guy so confident and strong-willed he stole a whole subseries from Mario from right under his nose. If anyone should star in a game all about the importance of overbearing personalities, it should be him.

From top to bottom, every aspect of WarioWare emphasizes the importance of individual contribution. The original grabbed me from the start largely because I could feel those personalities emanating from it so strongly. The strange art, the scattered sense of humor, the variety of the games – when I was younger I would call it unique because I had never played anything like it. These days, I’d call it unique because of all the wonderful contributions made by all of the unique individuals that worked on it.

Games like WarioWare that celebrate the individual are important. It often feels to me like people forget that real people work on video games. Not just the super famous higher-ups like your Shigeru Miyamotos; the people who do the art, music, programming, or even just had one weird idea that made a noticeable difference. We’re living in a time where team sizes on video games have ballooned, and the individual contributions have become less and less pronounced. In my ideal world, I would like for everyone who works on games to be a little more like Wario and have the opportunity to make their contributions clear, confident, and powerful.

Comments (0)